Testing for jQuery Users

Why and how to test your javascript code, using Mocha and Chai

If you’re at the stage you’re writing javascript using jQuery and have heard of TDD, BDD or Unit Tests and wondered how to get started, or why you should bother, this article should give a gentle introduction.

I always wondered why (especially if you worked with a test team), you needed to test your code at all. And how you could test, if you were building a web page whose success or failure was only shown by out of place HTML?

I have been introduced to three types of testing

- Unit Tests (represented by ‘TDD’ - Test Driven Development)

- Behavioural Tests (represented by ‘BDD’ - Behavioural Driven Development)

- Integration Testing

Integration testing was the testing I always thought was a bit odd to try with jQuery - large scale, full system testing. If the page looked wrong you just needed to see it. If a user clicked something, how would your test know? A user could just do anything! It was bewildering.

There are automation services, such as Selenium that can aid in that process.

At a much simpler level, a developer who is used to enhancing a web page with jQuery can add in tests to make sure those enhancements work, using Unit and Behavioural tests.

Why test?

Once you’ve built your site, pretty much anything can happen - clicks, hovers, dynamically loaded content and then in a variety of browers. How can you cover it all? Where to start?

The key for me was to accept that you can’t cover it all. You can, however, test parts. Then at least you’ve tested something.

Why test? Because you may not be the only person working on the code - if you have a test, then they can tell if they’ve broken it. You may be the only persion working on the code. In six months’ time you want to know if you’ve broken it.

Even the simplest of web pages can be quite stateful. For example if you’re fetching a parameter from the URL, say, then there’s a lot to bear in mind:

- Does it have no parameter at all?

- Are there many parameters?

- Is the parameter you require there?

- What if there’s a hash value?

To ensure your simple parameter function works, you’d need to go through each of those steps to check your function was working. If you’re thorough, you need to go through each of those steps every time you change a related part of your code.

If you’ve written tests, you only need to refresh your test page.

How to test

Take our fetching-a-parameter-from-the-URL example, it’s straightforward to write what you’d expect the function to do in those situations:

- Does it have no parameter at all? You’d expect the function to return null.

- Are there many parameters? You’d expect the function to return the correct parameter value

- Is the parameter you require there? If not, you’d expect the function to return null.

- What if there’s a hash value? You’d expect the function to ignore it, as we’re interested un URL parameters.

Notice that you’ve got a few things your function might do before you’ve even started writing it. In fact, writing the function is the last thing you’ll do.

How to set up your test harness (with Mocha)

Firstly, you need some code that will test your code. I’ll be using Mocha and Chai.

I’ve set up a repository on github for the examples used in this article. Feel free to download (or fork if you’re up to speed with github) and try things out locally. The github website makes it very easy to browse the code.

Your tests need to live somewhere separate to your code, but have access to it. So if you have a site with an index.html and a script.js, create a test directory, and add in an index.html and test.js files.

index.html

script.js

- /test

index.html

test.js

- /lib

mocha.js

chai.js

mocha.css

Let’s have a look at this. index.html and script.js are your site code (yet to be written).

/test will contain all your tests. You’ll need an HTML file for each set of tests (or all of them) and a test.js file containing your tests. We’ll come to that in a bit.

The lib folder contains the library files for Mocha and Chai available as mocha.js here, and the Chai file here.

The mocha.css file makes your test page look nice. It’s available from the same location as mocha.js. It’s probably a good idea to get that.

You can see the code in this empty outline structure at this commit in the test tutorial repository.

Now add in the code to make it go:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Mocha Tests</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/test/lib/mocha.css" />

</head>

<body>

<!-- Where the output is displayed -->

<div id="mocha"></div>

<!-- Libraries -->

<script src="//code.jquery.com/jquery-latest.min.js"></script>

<script src="/test/lib/chai.js"></script>

<script src="/test/lib/mocha.js"></script>

<!-- The code you want to test -->

<script src="/script.js"></script>

<script>

// Ask mocha to set up with the BDD interface

mocha.setup('bdd');

</script>

<!-- Your test code -->

<script src="/test/test.js"></script>

<script>

mocha.run();

</script>

</body>

</html>

You can see this code in the repository.

So, if you load up that page, you’ll see nothing happens - which is good.

We have no passes, no failures and no duration. Probably as we have no tests and no code.

Writing your tests (with Chai)

Time to start writing the tests for our function to fetch parameters from a URI - let’s call it getURIParam.

Let’s start by writing the test outlines. Here’s what we thought the function might need to cover:

- Does it have no parameter at all? You’d expect the function to return null.

- Are there many parameters? You’d expect the function to return the correct parameter value

- Is the parameter you require there? If not, you’d expect the function to return null.

- What if there’s a hash value? You’d expect the function to ignore it, as we’re interested un URL parameters.

In the structure of a mocha test, you’re describing the function, what it should do in certain cases and what you’d expect as a result. So:

describe('#getURIParam', function(){

it('should return null if there are no parameters in the URI', function(){

assert.ok(false, 'test not implemented yet');

});

});

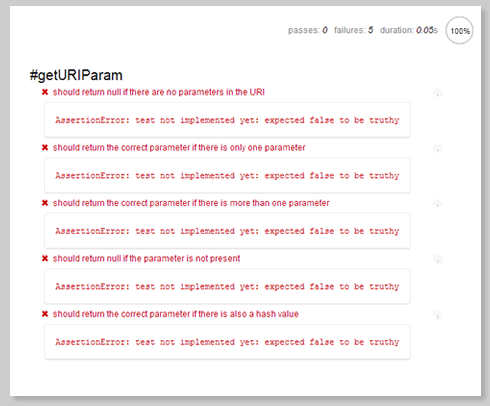

Note I’ve put in this line assert.ok(false, 'test not implemented yet'); That’s a handy placeholder that (counter-intuitively) always fails - if there was no placeholder, the test would pass. If we get a failure for a test, we know there’s something to be done.

Other than that it reads as english. I’ve filled the rest in at this commit in the repository

Everything’s failing. Good. Now let’s start fixing that…

Accessing your function

Let’s actually write some code now. I’ve added in my html file and my javascript. I’ve added the getURIParam function, but it’s empty for now.

Here’s the HTML

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>My get URI parameter page</title>

</head>

<body>

<label for="param">Enter a parameter to find in the URI</label>

<input type="text" id="param">

<input type="button" value="Find in URI">

<script src="//code.jquery.com/jquery-latest.min.js"></script>

<script src="/script.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

It will output whether or not the parameter entered is present or not in the page.

Here’s the javascript

var mySite = (function(window, $){

"use strict";

var self = {

getURIParam : function getURIParam(uri, param){

}

};

return self;

})(window, jQuery);

You can see that I can access my function using mySite.getURIParam.

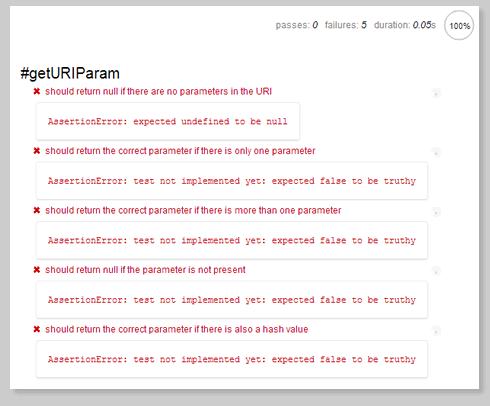

I can now add this function call to my unit test.

it('should return null if there are no parameters in the URI', function(){

var url = 'http://www.example.com/index.html',

param = 'test';

expect(mySite.getURIParam(url, param)).to.be.null;

});

A couple of things to note here: firstly the Chai syntax - it reads as english. You could pretty much guess the syntax and it would probably do what you imagined it would.

Secondly, note we’re not actually reading the URL from the page location. We’re testing the function, not the whole system. That’s really the key to unit testing.

The full set of tests are on github at this commit.

Looking at these now, you might see other possible tests. What if there’s no filepath? Or if there are parameters, but the one requested isn’t present. Maybe your code needs to cope with the parameters being in any order.

You can write Chai assertions to cover these cases - writing the tests can make your coding more thorough and robust.

Writing the code

Finally! We can start filling in the function.

It needs to return something, and I’ll initialise that to null:

getURIParam : function getURIParam(uri, param){

var val = null;

return val;

}

If you run the tests now, the tests for no parameters and parameter not present pass, hooray! Of course that’s really a false pass as we’ve done nothing.

I’ll get the search value from the uri string, and the parameters as an array from that search value:

getURIParam : function getURIParam(uri, param){

var val = null,

search = uri.split('?')[1],

params = search.split('&');

return val;

}

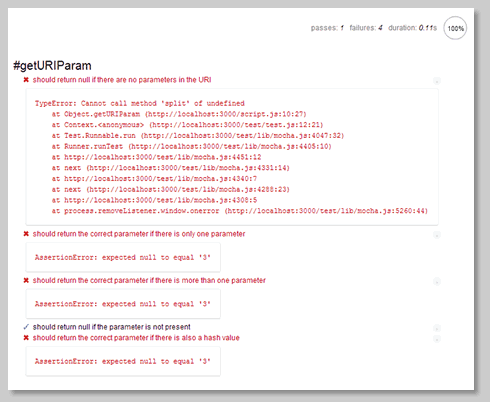

Immediately we can see a problem. Thank goodness for those tests!

We can see that the first test has failed completely. We’re splitting search, assuming it’s an existing string. If it doesn’t exist, we should be returning null (test 4).

Returning to the code:

getURIParam : function getURIParam(uri, param){

var val = null,

search = uri.split('?')[1],

params;

if(typeof search === 'undefined'){

return null;

}else{

params = search.split('&');

}

return val;

}

That’s better. Tests 1 and 4 now pass, but we can be sure that at least test 4 is passing meaningfully.

Changing the code to

getURIParam : function getURIParam(uri, param){

var val = null,

search = uri.split('?')[1],

params = []; // Given an initial assignment

// to set Array type

if(typeof search === 'undefined'){

return null;

}else{

params = search.split('&');

}

if(params.length === 0){ // check for any parameters

return null;

}else{

for(var i=0;i<params.length;i++){

console.log(params[i]);

}

}

return val;

}

Now tests 1 and 4 pass meaningfully, but I’m still thinking of potential issues - what if we have an &, rather than an & in the uri? Would our code cope? What if there’s no uri at all? Or a param has not been passed in?

I’ve added a console.log in the loop over the parameters I’ve got from the uri string.

test=3 script.js:22

item=003 script.js:22

name=dan script.js:22

test=3 script.js:22

item=003 script.js:22

name=dan script.js:22

amount=3 script.js:22

item=003 script.js:22

name=dan script.js:22

test=3#inPageLink script.js:22

I’d like to get the parameter value before the equals sign and if that’s the one we’re looking for return the value.

Here’s the for loop with the code I’ve replaced that console.log with:

for(var i=0;i<params.length;i++){

var arr = params[i].split('='),

key = arr[0],

value = arr[1];

if(key === param){

return value;

}

}

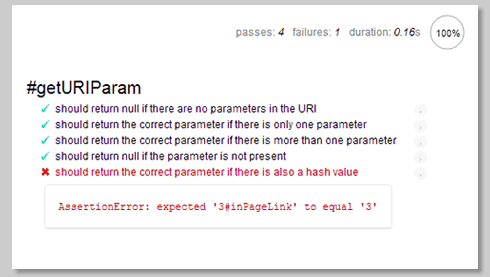

And here’s the output:

Much better! All done, bar one failing test - what to do when there’s a hash value.

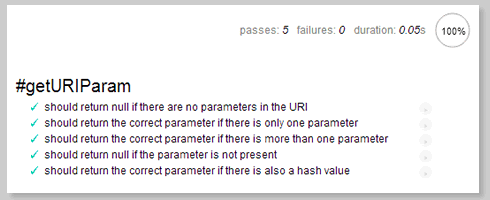

If I change the return to strip off everything after any # symbol:

return value.split('#')[0];

All tests pass!

You’ve now written unit tests for a simple function.

I imagine the function could be written better, with more tests - the code is here - feel free to play.

By the way, don’t use this function in a real project - I’ve noted how there are missing tests, and missing functionality, it’s illustrative only.

Why and When to Unit Test?

Testing makes your code simpler and more reusable - you have to break your code into ‘units’ to enable testing, and by doing so, your code becomes modular.

Test when you have a simple piece of code that has to cater for many situations, as in the example. It’s not such a good idea to Unit Test with DOM manipulation and user interaction - that’s what behavioural and integration tests should cover.

When not to test

It takes longer initially to get something up and running in a project if you’re writing tests. However, they can dramatically reduce bug fixing time.

To reduce that start up time, you really need to be sure that you are writing Unit Tests only for functions that require them - those manipulating or transforming data.

You don’t need to ensure behavioural tests cover every state in your system. Be judicious in your choice of tests.

If you get a bug, write a test to cover your expectation in the situation that causes the bug. E.g. if adding in a #! sequence breaks your url parameter getting function, then write a test expecting what should happen in that case.

Finally, ensure your tests don’t just cover the ‘happy path’. You need to ensure you’re testing beyond ‘what just works’, and also consider what might break your code and test for that.

Wrapping up

That’s Unit Testing - testing the function in isolation. In the next article, I’ll be using that function in the HTML, and using Behavioural Tests (and finally some jQuery) to test what a user might actually do.